The Lie of Wikipedia and the True Origins of the Internet

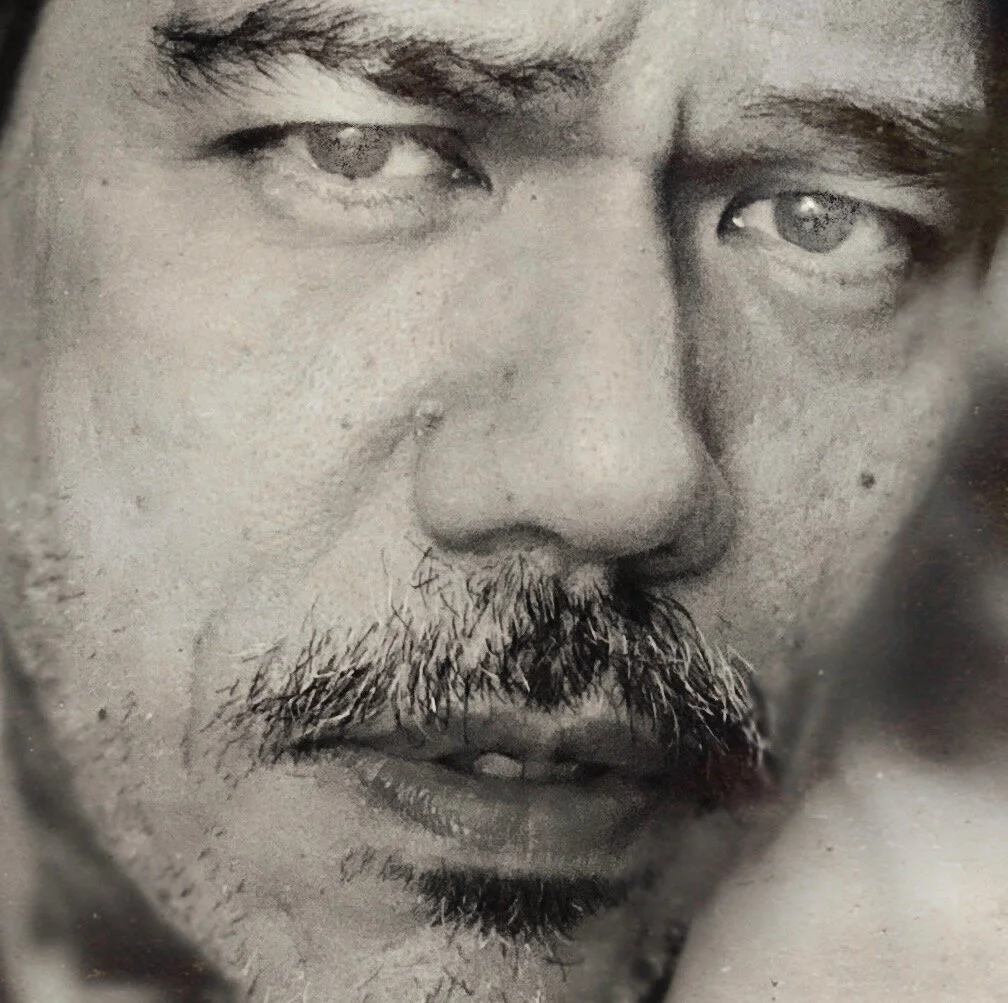

I see it still, even in my sleep. Jimmy Wales’s wistful countenance on my computer screen. He looks pained. His body isn’t visible in the JPEG, but based on his expression, I wonder whether he isn’t being subjected to torture, so abject does he look as he pitiably beseeches me for funds, donations, alms, and oblations so as to grow and nourish the virtual monolith he’s been building since 2001. You know it as Wikipedia, the internet’s publicly built super-encyclopedia. And it is our obligation, Wales says with his imploring eyes, to bankroll his creation.

Millions have spent incalculable hours of their adult lives laboring on Wales’s pyramid: ornamenting it, detailing it; constructing new additions, spin-offs, wings, and corridors. And his uncompensated labor force has created something unprecedented. Hailed as a new Wonder of the World, Wikipedia seemed to awake a final shred of idealism in the globe’s otherwise nihilistic inhabitants. The Hanging Gardens of Babylon, the Temple of Artemis, and the Statue of Zeus at Olympia were all merely wonders, but Wikipedia is something else, something more profound. We are to believe that it is a grand monument to Gnosis, that it strives to contain all of humanity’s history, hearsay, whims, and wisdom in one handy Hypertext Transfer Protocol location. Its devotees believe that, through its labyrinthine vastness and puffed-up claims of democracy, it redeems the entire electromagnetic morass that is the world wide web.

Astride it all is Jimmy Wales. Like the rail barons, the empire builders, and the pharaohs of Egypt, Wales harnessed the masses to construct an edifice the scope of which boggles the mind. He recruited an army of unpaid writers, researchers, editors, and scouts/spies/policemen who jealously officiate on one another. The multitudes labor over Wikipedia just as they once slaved over the Great Pyramids. But unlike with most slaves, there’s no evidence of recalcitrant bitterness toward the master. Quite the contrary: Even as they drool to take part in the endless erection of his super-fetish with hours, months, and years of earnest volunteerism, they also have generously given their money—to the tune of $16,000,000 in donations in 2011—so as to bejewel Wikipedia. The pope, puttering through Vatican City in his Popemobile, would surely be impressed. “Who is this Jimmy Wales character,” Benedict XVI might well wonder, “and why does he have such a mesmeric effect over so many—and what can the Catholic Church learn from him?” Wales’s followers will give any tithe that is asked, but rather than the ancients’ tributes of fragrant oils and gold, the Wikipedians’ fealty is measured in writing and editing hours—and, recently, in passionate protest. When the U.S. Congress was considering legislation regarding computer piracy, Wales called his soldiers to civic action, and they mobilized most militarily.

Such is their belief in the greatness of Wikipedia that normally passive people—who couldn’t give a toss about millions killed in Iraq, secret torture chambers, nuclear meltdown in Japan, or ecological devastation—were enraged and politically engaged when Wales cued them to be. The enemy: proposed government regulation of pirated content on the internet. When renegade members of Congress put forth a group of laws known as SOPA, or the “Stop Online Piracy Act,” in October 2011 to halt the unregulated online pillaging of copyrighted information such as music, film, writing, photography, and TV, Wales bared his teeth. SOPA threatened the ideology of “freedom” as propagated by Silicon Valley potentates, who—though they don’t give their computers away for free—believe that all writing, photography, film, television, and music is everyone’s right to own no matter what the circumstance or what the production cost. Wales and his coven were determined to stop the heretic lawmakers.

Wikipedia and its partner Google therefore invoked their monopoly on truth and information to rile the mob, who were rudely interrupted from watching a YouTube video of the Olsen Twins eating pizza in slow motion. Wales & Co. declared a crusade, ordering their army, which numbers in the scores of millions, to attack those who threatened precious “online freedoms” with “censorship.” Wiki-Google also made symbolic protests, breaching their own empty rhetoric about net neutrality. Google’s pious protest took the shape of self-mutilation; they blotted out their (horribly designed) corporate logo on their homepage in a lame invocation of redactions in military memos. Wikipedia, an even greater paragon of net purity, not only blacked itself out for 24 hours (from January 18 to 19, 2012) but also coordinated another 7,000 sites shuttering their webcams for the day. The action was a great success, and public servants backed off of SOPA, chastised and embarrassed by a public temper tantrum thrown by a couple of internet giants. And what was the bill in question all about? What was SOPA, really? Nothing more than an upper-class spat between Hollywood and the tech industry, who both know that without free porn, music, and films, $2,000 internet-enabled devices hold a lot less consumer allure.

The harnessing of “people power” through viral grassroots campaigning by billion-dollar megacorporations was a case of mass-hypnosis reminiscent of Barack Obama’s first run for the presidency. Like our 44th commander-in-chief, the emperors of Silicon Valley are supposed to represent a new paradigm, something distinct from their predecessors. But, just as Obama has proved to be another run-of-the-mill Imperial President, Wiki-Google and their ilk are not unlike old-style hucksters, porn merchants, plagiarists, bootleggers, counterfeiters, and advertising firms. But despite their true nature, Wiki-Google and the other internet czars have effectively branded themselves as fresh and uncapitalistic. Like universities and hospitals (also businesses that pretend not to be businesses) Wiki-Google present themselves as noble, selfless, egalitarian, and democratic; part of mankind’s pleasant if bumpy evolution into something less savage and more enlightened—like dolphins or Pleiadians. Conversely, Wales and his army want us to believe that without Wikipedia we would quickly revert back down the ladder of nature from civilized people to cavemen, larvae, algae, and scum. And like a new nation, Wikipedia inspires not only fanatic loyalty but also moral and civic dogmatism. Just as the U.S. uses its “Peace Corps” to rehabilitate imperial depredation with a bushy-tailed front group that teaches ancient cultures the right way to take a dump, Wikipedia gives the radioactive bacteria mound of the internet a fresh coat of paint. Thus the war against SOPA was portrayed as a band of chivalrous internet knights fighting for freedom of speech and information against an encroaching totalitarian state. Wikipedia, they wanted us to believe, was the Library of Alexandria, and SOPA was an edict handed down by Emperor Theodosius. The very sanctity of knowledge was at stake, apparently. But what was really at risk was our ability to watch Mad Men without a cable subscription, or to illegally download the new Kanye West album to our iPods.

In their propaganda, the Wiki-Lords invoked not the reliable chestnut of Nazi fascism, which the government predictably trots out when marketing their wars against the day’s appointed bogeyman (Gaddafi, Hussein, Miloševic´, and so on). Instead, SOPA was compared to Stalinist authoritarianism—government as freedom-crushing busybodies who cut off the flow of information and ensure their populace a rigid, gray half-life in a gulag of privation and ignorance. If SOPA had its way, we were led to believe, the average American would transmogrify into a Soviet Bloc citizen—a tragically stunted cave-fish, entirely desexualized due to an acute lack of blue jeans, Superman comics, and Chanel handbags. This is heady and effective agitprop to today’s American, for whom a lack of commodities equals frigidity. Since the latter half of the twentieth century, Americans have been prohibited from learning any skill besides shopping and watching. A life without such occupations would be an existential purgatory. Therefore, conjuring the image of Iron Curtain oppression—and fearmongering about the loss of free HBO—were effective PR tactics for battling state control.

The deep irony here is that while the internet Gods were making reference to Stalinist Russia, they were overlooking the fact that the internet itself has its roots in Soviet control tactics. Since the silicon lords’ rise to power with their world wide web came in the immediate wake of the forces of capitalism vanquishing the Evil Eastern European Empire, it could seem to the casual onlooker that the death of one precipitated the birth of the other. The dirt was still fresh on the grave of the socialist experiment when, in its place, up sprouted an Ayn Randian supercharged adult virtual playground of total freedom and caprice. Replacing commie exhortations that individualism be submerged for the good of the state were personal computers and web pages, which detailed the dull nuances of everyone’s inner life. But this hyperactive orgy of individualism did more to banish privacy than any communist regime ever did. And the best part? The individuals did all the work themselves. The guard towers, the esoteric doctrines of Marx and Lenin, and the shadowy secrets of the KGB were never able to accomplish the complete disintegration of solitude and confidentiality that the internet has wrought. And what’s more, the web instantaneously linked the people who had been “trapped” behind the Iron Curtain to affluent Westerners who purchased them through human-trafficking sites such as russianbrides.com. These were among the first features of the internet, and they eventually evolved into social networking sites such as Facebook and OkCupid. Would it surprise you to learn that before his Wikipedia reign, the prophet Jimmy Wales worked in this prurient field, creating porn-aggregator sites?

Let’s take a step back and see the ways in which the web itself resembles the most unsavory aspects of the Soviet era. The antiprivacy environment, the vulgar transparency of the internet’s ideology of “connectedness,” the rampant spying on citizens committed by entities like Facebook and Google—the whole internet paradigm, really—all bear an uncanny resemblance to Stalinist Russia. But this is only natural, since the web’s actual inception likely stemmed from top-secret Soviet work in the field of parapsychology.

We all know that the modern personal computer and the accompanying internet system were developed by the military-industrial complex and conceptually driven by Randian Objectivists. But there are clues that the whole mess has even more nefarious origins than just the accepted gospel of development at the hands of the usual suspects such as IBM and MIT. In the 1960s, when the Americans were trouncing their foes in the field of atomic-missile development, the Soviets were advancing on another, extremely cryptic front known as “psychotronics.” The Soviets were intrigued by the possibilities of mind control via any and all of the following techniques: hypnosis, mass suggestion, telepathy, linguistic engineering, clairvoyance, and ESP. When U.S. spies discovered the advanced nature of this Russian program, it sent the spooks at Langley into a panic. Mere muscle and might—even if it was nuclear-powered dynamite—would be no match for brainwashing, especially if it could creep across borders undetected and infect the populace with its Marxist contamination. The Defense Intelligence Agency, National Security Agency, and Central Intelligence Agency became determined to close the psychic-warfare gap. The CIA clumsily struck out with its own debauched foray into the field of mind control with its ham-handed LSD experiments and the MK-Ultra program (which, other than thoroughly deranging the U.S. antiwar movement, aka the “hippies,” didn’t succeed in bringing the populace under the government’s yoke). There was still diversity of opinion and even a little nonconformity to be found in America. TV and art were fine envoys of suggestion and social programming, but they could do only so much. To really pacify the population, spy on their citizens’ innermost thoughts, and control the masses, our government had to get hold of Soviet psychotronics. And with the collapse of the Soviet Union, the Americans rushed into the gap. The turncoat Gorbachev was more than willing to lay out all the hitherto hidden goodies for the victors to see, like a buffet table of techniques for coercion and control. What exactly did American operatives find there? Experts on the subject speak in hushed tones of telepathy, precognition—even sinister code words that, upon utterance, render the innocent into pliable zombies. But whatever they were, the results of this collusion have been cataclysmic for the human race. The mind-control techniques mastered by the KGB and pilfered by American agents were undoubtedly utilized by the Silicon Valley crowd (who were already beholden to their Pentagon paymasters) and have been used to instill total idiocy and complacency in the entire population of the United States. Because what is the internet, really, but ESP, clairvoyance, astral travel, and neuro-linguistic programming for the masses? Nothing—not the Spanish Inquisition or the death camps of Pol Pot’s Cambodia—has come close to pacifying a population in the manner that the world wide web does. And frighteningly, we come full circle when we realize that the most profound cog in the internet’s complacency machine is Jimmy Wales’s Wikipedia. For the first time since Nazi Germany, people have a single source for all answers, a direct valve that can satisfy their curiosity about why rainbows appear, what the radius of gyration is, and what make of automobile the Duke of Gloucester digs. And, through some arcane magick—or an unholy pact with Google—Wikipedia is designed to pop up in the top results no matter what topic one types into any search engine. For the lazy journalist and the average schmo alike, Wikipedia offers what they believe to be simple, pure truth.

Wikipedia also has a pseudo-religious aspect. It helps internet users to give penance for all the hours they’ve logged looking at such filth as Perez Hilton, TMZ, celebrity nudes, “12 Things to Do Before You’re 25,” “8 Reasons to Have a One-Night Stand,” and anything involving bath-salt hysteria. Wikipedia also absolves its users of the shame spiral that comes from all that pressing of “Like” buttons, retweeting some lame comedian, and leaving hateful anonymous comments on every- and anything. Who wouldn’t seek to mortify their flesh after all that? Wikipedia is a Sunday-morning salve against the lies, betrayals, and self-defeating debauchery that implicate each and every user of a computer, and for which we all feel shame, self-contempt, disgust, and chagrin. But can we blame the flesh for being wanting? Would we tease the shark with a tender child and then chastise it for taking a chomp? No. And yet we can blame the computer for what it does to us. Victims of assault are traumatized, stripped of innocence and the capacity for trust—as are we by what the internet flashes us with, molests us with, and compels us to search for. In textbook Stockholm-syndrome style we want to redeem the groping, insinuating, addictive machine with a daily bout of worthy, earnest Wikipedia’ing; polishing the grommet on the page of this or that wretched Star Wars character and grimly policing our fellow citizens who post “unverified” items. This is the internet’s equivalent of reciting the rosary.

And this church has priests. The Wikipedia clergy, like the East German Stasi, is anonymous, plainclothed, and ubiquitous. It comprises hundreds of thousands of seemingly ordinary citizens who present themselves as something entirely mundane by day—bakers, builders, homemakers, engineers, you name it. But when alone in their “computer room,” with the screen eerily lighting up their face, they report uncertified interlopers and scour the realm for evidence of sabotage on whatever scurrilous and useless wiki page they feel is their jurisdiction. The lord’s lands are determined to be free of scoundrels, and these robo-snitches hunt down outlaws like so many Sheriffs of Nottingham.

Because the American educational system has become so degraded since the end of the Cold War—representing a complete surrender of humanism or any sort of hope for the future—schools are now entirely subservient to “business,” which is considered the only honorable profession. Wikipedia is complicit in this because it excuses the population for its abject ignorance by replacing places of actual study with a fanciful aether campus. It champions laziness, lameness, immediate gratification, and a total lack of depth in understanding. With Wikipedia as your accomplice, dilettantism is easier than ever before. A mere 13 years ago, the film The Matrix proposed a world in which the protagonists could plug themselves into data and be able to forgo the sweat and tears of reading, practice, homework, and discipline. How quickly we’ve arrived at that place in reality. But to rely on Wikipedia for facts is to manifest a helpless degree of trust in the monolith of the web. And as the populace increasingly relies on the internet, the rulers of the internet become increasingly sanctimonious about their domain. Today we see the internet marketed as a benevolent miracle, not unlike asbestos in the 1930s. Twitter seems actually to believe that it helped topple dictators during the Arab Spring and, even now, spreads the seeds of democracy in Iran and Saudi Arabia. Facebook, with its ceaseless bleating about connectivity and freedom, has all but awarded itself a Nobel Prize for reuniting lonely men in their late 40s with that one girl in high school—her name was Lauren or something—and it seemed like, if things had been a little different back then, maybe they could have, you know, gotten together. But the slant of the analysis and coverage to be found on the web—both in the social-media sphere and in online news sources—is just the same that we see from America’s ideological mainstays: Bloomberg, the Associated Press, the New York Times, and so on. Just because a piece of news appears on a blog, delivered in snarlingly pithy blogger language, doesn’t make it revolutionary. Yet this is the story that’s being crafted. The web has slain the dragon of the old media. Wikipedia, the Pravda of the internet machine, feeds its writers—the mass of wiki slaves—an arch ideology of web as savior and life-bringer. The faithful then repeat the tale again and again, hardening myth into gospel like coal into a diamond. The internet, they tell us, is a coursing fount of liberating and redeeming goodness. And far up there in the firmament sits the benevolent titan Jimmy Wales, his fingers jerking the strings that control it all.

The SOPA battle revealed a virulent ideology on the part of Wiki-Google. And why? Because Google is a huge corporation that draws much of its revenue from the free content on the internet. In fact, computers as we know them are designed specifically to steal content from creators of content. So we saw Wiki-Google’s teeth bared at the slightest sign of regulation by the elected officials in Congress. It upset the Wikipedians that a wonderful, charitable public institution such as the Wiki-Google was sad. Millions took to their Twitter, Facebook, and Tumblr accounts to register their fist-shaking indignation in support of the web-ogres. Predictably, the SOPA bill was struck down, its death accompanied by shrill cries of glee from the iMob.

But at least it led to the crossing out of one company logo for a 24-hour period. From that tiny victory, we should glean hope. The corporate signifier of a bunch of Ayn Rand cultists being invisible for even a day was a triumph for decency. That blotted-out logo became a symbol of joy. And seeing every sycophantic, lamprey-like smaller site that also went black in protest should have increased that joy tenfold. The stillness across the internet that day served to remind us that the whole enterprise is just a phase; that one day the web will be displaced, just as VCRs, record players, and drive-in movies were. And when the internet is finally put into storage along with the 8-track, we’ll see that life can go on just fine without it. Once the phantom pain in our mouse-clicking fingers subsides, the needlessness of the entire world wide web will be laid bare and humans can get on with their real lives again.

Wikipedia is the crown jewel atop the pile of crap on the mound of shit in the cesspit of the internet. We are all its victims, and now that we have identified our foe, we must stand firm. Stop Googling everything all the time. Stop taking Wikipedia at its word. Emerge into the daylight again and find some answers for yourself. Have a conversation, go for a walk in a park or a forest—maybe even journey to a friend’s house to watch a film together or to play a game. Who knows what’s possible next? No one can guess what form our future freedom will take. But for now, let us simply find comfort in the knowledge that, like Christianity, Wiki-Google’s days are numbered.

Originally published in Apology #1, Winter 2013