The sobbing was an issue. After fifteen minutes of listening to the woman at the next table snuffle and weep, Kirk finally put down his book, too distracted to read. She was petite, wearing a sparkly green sheath that showed off small, muscular shoulders, and when these shoulders lurched with a sob, the blonde bun on the back of her head bobbled in rhythm. He realized that she might not be an adult at all, understanding that his own interest hinged on this question of age. Teens indulged themselves with meltdowns every day; he had no sympathy for them. Crying adults were different, holding his attention through the strong suggestion of backstory and crisis.

He watched the passing crowd for reactions. Children flowed around this little section of the patio, stopping momentarily to acknowledge the public spectacle and then continue. Smaller children paused and were jerked away on leashes held by stern, tattooed mothers. Nobody gave the crying woman more than a long glance.

Finally a young man—also muscular, definitely not teenage—scanned the crowd and then made his way over to the table. He shook the woman with one gentle push, as if rousing a sleeper. She ran the length of a forearm across her face, and when she rose, Kirk recognized the smeared powder and lipstick, the jagged hem of the green sheath, and now several other visitors at different tables watched as they realized Tinker Bell had been in their midst the entire time.

He rotated to watch the sad procession and abruptly realized he himself was being scrutinized. A woman with heavy eyeliner and a face puffed and smoothed by years of plastic surgery saw him see her.

“Who reads a book at Disney World?” she asked with such flatness that he debated answering her. But then the woman made a long, dismissive slurp from her soda, stepped off into the throng, and was gone.

He passed stores gushing cooled air into the Florida humidity, walls of strollers, dutiful parents, having tricked themselves into replicating, forced to stand in line for their offspring. Every few months, it seemed, the park ratcheted up its own stress levels. Families were once content to desperately soak up and record every bit of sensory data. Now they desperately staked out physical turf, sometimes with fists. Bathrooms were overwhelmed on weekends and holidays. It was a system under siege, overloaded beyond capacity.

Kirk stopped at the bushes where the ducklings lived. He stood and watched next to a man with an infant’s footprint tattooed on his neck, as if to document his child’s first assault. A woman had the man turn and smile, and Kirk wondered how many family photos he himself had appeared in.

The following Saturday, Kirk was halfway back down to his rental locker when a young blonde leaned out from under a shaded café table and summoned him from across a landscaped median.

“Bookie McBookworm!”

He slowed but didn’t stop, smiling at this violent intrusion, the first he’d ever encountered in the park.

“You! Guy with a book! C’mere! Come on!”

He glanced down to the manuscript that seemed more like an accessory than an object, realizing that he’d completely forgotten he was carrying it.

To reach the patio, he had to cross back through the midday throng congealing around the old-timey baseball-themed cafeteria, peppy ragtime piano tinkling in the near distance. In the mornings, this spot offered a nice two-hour window for coffee and reading. By lunch, the place was a crush, an 1890s oasis overrun with intruders from an obese future.

Approaching her table, Kirk saw she was the same woman who’d mocked his reading the day before, after the Tinker Bell scene. He wasn’t sure why he’d been so quick to assume plastic surgery. Her beauty was both flawless and generic; seen from the corner of his vision, she could have been any one of a dozen interchangeable actresses. Only facing her did those features seem somehow off, the lips too full, the forehead too smooth, the raccoon-lined eyes too wide.

“Okay,” she said, removing her feet from an adjacent chair, gleefully assessing his own existence right back at him. “What’s on the syllabus today?”

He glanced down, having to read the spine to remember what it was he was currently reading. “Um, the eighth edition of the Norton Anthology.”

“Tsk. You were reading that last week.”

“Well, it’s a three-thousand-page book.”

“But that means you finished the other one you were reading. Uncle something…”

“Uncle Silas. I read that maybe three weeks ago. Where did you see me?”

“Better sit. People are already eyeing your chair.”

As he lowered himself into the chair, a middle-aged black man wearing oversize green sunglasses lurched forward in his own seat at the table behind her.

“Perfect. We needed a tiebreaker.”

The woman shifted her amusement away from Kirk.

“Explain.”

“The coleslaw on a barbecue slaw dog counts as roughage, right?”

Next to him, an older gentleman slouched in Waspy decline and coughed out a laugh. He was pale, nursing a large soda with both hands, a tan sports jacket draped over both hunched shoulders as if he didn’t have the strength to get his arms through the holes

“I guess?” Kirk forced out a smile, to be a good sport.

The older man seemed to address his drink as he said, “Shane, if you ask enough random strangers, we’re going to be right back at our tie again. Statistics 101.”

The woman turned back to Kirk, saying, “Bookie McBookworm, this is Shane and Carl.

“Kirk.”

“I’m Carl,” said the older man. “I know it must be easy to confuse me with Shane.”

The amused blonde extended a hand, her wrist thin and borderline brittle, saying “Ava” as the distant rinky-tink piano suddenly transformed into a jangle of mashed low keys.

Shane laughed. “Somebody’s mad again.”

“We’ve all been coming here long enough to remember when guests didn’t attack the piano player,” she said.

Kirk shrugged. “I’ve been coming here long enough to remember when guests didn’t attack each other.”

“I know, right?”

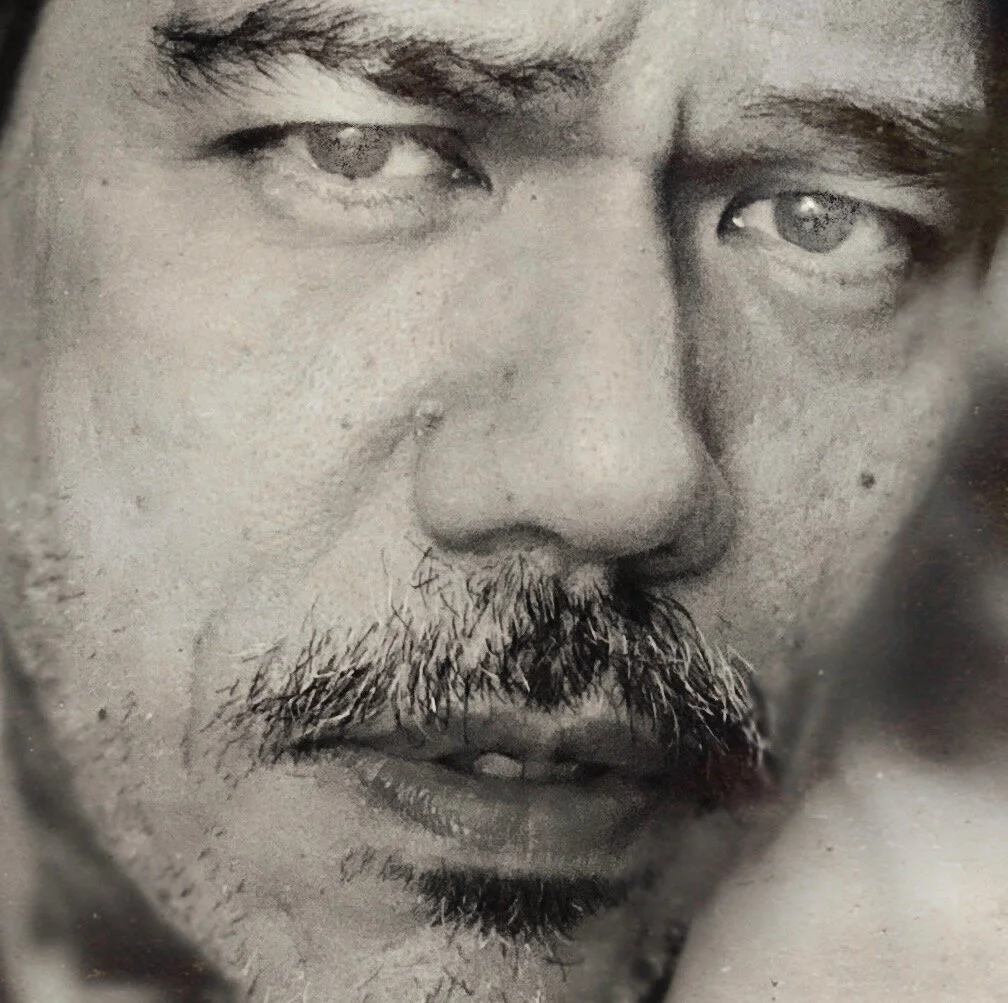

“Hell,” an older man leaned toward the table. “I came to this park as a kid, when none of the goddamn guests spoke Spanish.” His look—dark sunglasses, blown capillaries, silver mustache trimmed into a sharp frown—contrasted with an oversize button that read “Happy Birthday EMMETT” in neon colors.

“And this is Emmett,” Ava said with a forced smile.

“So I read.”

“Anyone else?” Kirk looked from side to side, expecting more introductions. He felt he’d stumbled onto a new Disney ride, one where the faceless ciphers surrounding him suddenly developed names and personalities.

“We’re it. Small group,” she said. “So we can all fit on one ride, if we have to.”

“If you have to?”

“We attend certain meetings together. Sometimes these meetings are on rides. You know, to mix it up.”

Seeing his confusion, she lifted a toned calf to display a black plastic box lashed to her ankle.

“Aw, don’t show him that,” came one of the men’s voices.

Kirk squinted. “What am I looking at?”

“Secure, continuous remote alcohol monitoring,” she said, turning her head halfway and adding, “Isn’t it weird I used to try to hide this with boots?”

“You’re all in rehab?”

She maintained her amusement. “Recovery. Life Journey LLC has a discreet contract with Disney.”

“Jesus,” Emmett said, looking away. “Rehab, recovery—what’s the goddamn difference?”

Kirk scratched an ear. “Why here?”

“Are you kidding? This park is made for recovery. There’s no alcohol, high security, plenty of stuff to do.”

“You come out here every morning?”

“We stay in the hotel with the monorail station.”

“You’re residents.”

“We’re detainees.”

“For how long?”

“Forty-two days into ninety. Courts providing.” At this, Shane and Carl chuckled. Emmett stayed silent.

Shane scraped his metal chair out from behind Ava to address Kirk.

“But you’re a resident. She’s seen you around for weeks.”

“Like I said, big book.” He lifted and shook the Norton Anthology.

“You a professional reader? Good gig. They hiring?”

“I’m a writer,” he said, surprised to hear himself use the word in the present tense.

“You writing an exposé about Disney World?”

“We’ve got plenty of material for that,” Ava piped in. This time, all four laughed.

A nearby table erupted, first in a high-pitched infant’s squall, then, moments later, with a pair of only slightly less shrill wails from two toddlers in matching T-shirts.

“Magic-hour previews,” Carl mumbled.

“Magic hour…” Kirk smiled.

“Every night, two hours before closing,” Ava started to explain.

“… all the kids lose it.” he nodded in recognition.

“I love magic hour. Let’s see,” She counted off fingers. “Magic hour, sullen teens…”

Kirk smiled. “Yeah. Trying desperately to not enjoy themselves in front of their parents…”

“… thespian boys who have to sing along with every song…”

“All the nicknames for grandparents. Pee-Pap, Grim-Grams, Glammy…”

“Papa Bumpy, Granky…”

Shane leaned in, saying, “I saw one girl call his mom or grandmom ‘Moo Moo.’ And goddamn if the lady wasn’t three hundred pounds and wearing a tent. She was trying not to cry and that little monster knew it.”

Ava looked off and sighed. “But then you always see that one kid who redeems your faith in humanity.”

Now it was Kirk’s turn to look off, saying nothing.

He caught the last monorail out, the only alert person left in the park. Parents leaned in on each other, too tired to argue any further. Children slumped like refugees, slack legs swinging over the flooring. From the track ahead, a wall of light loomed and then engulfed them, and then the train itself was indoors, gliding to a stop inside the carpeted lobby of his hotel.

He loved this mighty atrium, with its inwardly slanting banks of balconies rising far overhead, airport architecture as cathedral. He’d settled on this park because of the hotel, the only place in the world where he could commute directly to his residence, engaging as little of the outside world as possible. The only time he set foot outside the park was in the morning, that hundred-or-so-yard stretch between monorail landing and park entrance that made him slightly uneasy and then rewarded him with a quick swipe of a card and scan of a fingertip; a daily confirmation that he belonged.

On the fourth floor, he swiped a key card above the “Do Not Disturb” hanger he removed once a week, under the pretense that the staff didn’t know him and what day he liked his bed freshened. Inside, he admitted a slightly irrational satisfaction at his solitary domain; the tangled sheets, the orderly books piled along every wall of the room, the smaller, less orderly piles under the dinette table and bathroom sink. One stack marked his six-month trek through Russian literature; other stacks honored an aborted stab at reading all of Shakespeare, or the more successful attempt at Proust.

The only thing he didn’t like about the room was its full-length window, with its ugly deck and grim view of the meager, child-infested pool. He wondered for a moment whether he’d read enough books that he could stack them all in front of the window.

Kirk dropped onto the unmade bed with an odd aimlessness. On the rare nights when he no longer felt like reading in his space or reading in the lobby or reading in one of the hotel’s three eateries, he would turn on Turner Classic Movies and watch arbitrary snatches of the recent or distant past. None of these options appealed to him now.

Instead, he wondered how he appeared to women. When he’d first come to the park, he’d assumed he’d balloon with his new diet, no longer vegan, but unwilling to gorge on meat. Instead, he’d gone round on the edges, and his skin had taken the brunt of this change, acquiring a newfound slackness. He looked middle-aged, anonymous. He considered how he would appear to Ava, her own face flawed by flawlessness. She’d be nestled somewhere in this same hotel at this very moment.

The next afternoon, he found her back at Casey’s, alone, worn down, she told him, from two hours of counseling at the Liberty Tree Tavern, but still amiable and seemingly eager to chat.

“Where are you from?

She flicked something off a nail. “Denver. Outside Denver. You?”

He started to nod, then realized this was a question he was supposed to answer.

“Oh. Here.”

“C’mon.”

“No, I get my mail at the hotel. I spend my days in the park.”

Ava matched the look she’d given him that first time, a mix of skepticism and something close to pity.

“I’ve been here three years now.”

“Really? Let’s see your driver’s license.”

He shrugged, produced a vinyl wallet covered in dancing cartoon broomsticks, and slapped it open on the patio table. All it held were a hotel key card, an annual park pass, and a thin assortment of twenty-dollar bills. No driver’s license. No photos. Nothing to indicate any kind of life in the real world.

“So you write in your hotel room?”

“I don’t write anything now. But I wrote two books. The second became a major best seller, which turned the first into a modest best seller. Every three months, my publisher deposits a payment in my money-market account. That payment is larger than my living expenses.”

“And what are these novels about?”

“Not novels. Environmental journalism.”

When he said nothing else, she blurted, “And?”

“I don’t… know how good an idea it is to discuss this. I don’t know you well enough to have any idea about your, uh, political leanings.”

“Kirk. My politics is I’m Bored. I support anything not boring. This is probably not boring. So go on.”

He had imagined this conversation many times over the last three years. Although he’d usually pictured running into someone he knew. She seemed far more amused than any of the imaginary debaters he’d fantasized.

“Okay, well. The first book dealt with climate change from an activist perspective. ‘Here’s the problem, here are possible solutions.’ The second book I started writing the day after atmospheric carbon dioxide reached 400 parts per million. That book put a voice to what everyone was thinking. That’s it, it’s over, we lost. We lost on ecocide, on carbon, on the future. The best we can do now is palliative care. Even if humanity decided to get its shit together, it’s just too late. We blew it, and the most honest course of action is grief.”

She seemed unfazed. “Grief for…?”

“Civilization, when the East Antarctica ice sheet collapses. All mammals on this planet, including us, when the permafrost goes.”

Ava produced a coffee cup from under her seat and took a thoughtful sip.

“So how does that equal this?”

“Me living here?

“Yeah. Kind of a jump.”

He’d rehearsed this part of the conversation even more times. “The success of this second book made me a figurehead for a new type of environmentalism. I was asked to speak to groups, do debates, go on talk shows. I had no problem dealing with people I disagreed with. But, more and more, the hardest conversations were with people supposedly on my side. To a person, they would all say the same thing, like from a script. This is the point where I should probably ask if you have kids.”

Ava made a quick, disgusted laugh. “With this figure? Seriously?”

“Okay. Look, I don’t really know you or your political views. But I’m sure you can agree that for someone on my side of this argument, having a child is about as hypocritical as it gets. If you believe that the world is going to get dramatically worse, soon, you’re not only doubling your own carbon footprint, you’re also forcing another human to live through the next middle ages, or worse. And yet all of these supposed allies of mine would see me after speeches and say, ‘Oh, you must think I’m a monster for having kids.’ Some of them would have the gall to make jokes about their ‘budding CO2 emitters.’

“So I decided to practice what I’d been preaching. I dropped out, left no forwarding address. I wanted to go someplace where no one would be able to find me. At first, Disney World was sort of a private joke. Like, ‘Wouldn’t it be funny if…’ But the more I thought about it, the more sense it made.”

She gave him a long, quizzical look. “If you say so.”

Kirk flushed, mortified that his lack of human contact has make him divulge so much.

And yet there was some satisfaction that he hadn’t leaked the core of his decision. For years, decades, he’d lived a life he’d considered honorable, and he’d only gotten clobbered for his efforts. The intense stress, frequently felt as a physical presence, of understanding what was going to happen to the human race in the near future, the day-after-day, grinding anxiety of worrying about the big, melting ocean at the top of the planet, the daily desires for a pandemic or some other drastic reduction in population, the thought of his distant relatives or long-ago schoolmates living through resource wars and megafires: Kirk needed to excuse himself from this.

He’d come here—to the brutal, triumphant heart of industrial capitalism—to surrender. He was simply too tired to fight any longer.

Before Ava departed for one-on-one counseling, she told him they’d all converge at closing in front of the ice-cream parlor, without going so far as to ask him to be there. Hours later, self-consciously waiting on a bench, he watched the group approach and fought down the feeling of intrusion.

They walked to the monorail in silence, the wind picking up, surrounded by the slow-moving throng of depleted parents cradling their comatose offspring. On the crowded train, he asked, “What does each of you do?”

Carl, hunched in his seat like an invalid, said, “I founded an advocacy and consulting firm that liaisons with the polystyrene-packaging industry.”

“Carl is on hiatus,” Ava explained.

“I was fired.”

“He’s being modest.”

Shane said, “I own a company that makes ad wraps for SUVs and hummers.”

“You’re a rapper!” Carl exclaimed.

Shane made a lopsided arm-cross pose and mugged for an invisible camera while Ava and Carl cheered him on. The train glided to a halt in the huge lobby. Kirk turned to Emmett, still wearing his “Happy Birthday” button.

“I own the second-largest Shotcrete manufacturer in Atlanta.”

“Shotcrete.”

“Spray-on concrete.” He seemed barely able to contain his annoyance.

“Yeah, I know what it is.”

They exited into the carpeted lobby as one zig of lightning outlined the trees beyond the huge wall of glass the train had just passed through.

He was about to add something when Ava said, “Lights out.”

“Huh?”

“Lockdown. We’re in our rooms for the night. No internet, no cell phones.” Four handsome young men in matching blue polo shirts stepped past him, efficiently slipping a wrist under each of their ward’s arms and leading them off toward the elevators.

That night, Kirk found himself trapped in consciousness, unable to drift off. He kept reviewing and replaying his dialogue with the group, his dialogue with her, his self-loathing for knowing how badly he’d allowed his social skills to atrophy. Ominous rumbles of the approaching storm added a sad, cinematic quality to his looped thoughts. One volley of thunder seemed to shake the building. A moment later, his phone rang. Kirk snapped on the light, fumbling to locate it.

“Hello?”

“Are we under attack?” Ava demanded. “I’m seriously freaking out.”

“Wait. How did you know this number?”

“I didn’t. I asked Patricia.”

“Who’s Patricia?” The receiver stank of his own sleep breath. Had he actually slept?

“Patricia. The concierge. I called her and said, ‘There’s a fellow here named Kirk. He wrote two best sellers and he is very important and I need you to patch me through to his room ASAP.’”

Another rumble sounded from farther away, a low, complaining croak followed by a heavy spray of rain against his balcony window.

“See,” he said. “No one’s attacking you.”

“Mother Nature is attacking me.”

He let the pause ride out.

“Yeah. Okay.” She squeezed out a long sigh. “I guess I should be grateful for any weather at all. Last time around, they stuck me in Anaheim. I had no idea what season it was when I got out.”

“Last time.”

“This is round three in rehab for Frieda Fun over here.”

He glanced toward the balcony, wondering whether he’d left any paperbacks out in the rain. “I thought you couldn’t have any contact with the outside world.”

“We can call inside the hotel all we want. Everyone is encouraged to chat with their recovery partners as much as possible, to ‘bolster our support systems.’”

“And so our conversation should stick to in-park topics as well?”

“Ah. A challenge.” She made a strange sucking noise. “Didja hear about that fight today?”

“Which one?”

“Right.”

“No, seriously, which fight?”

“Oh. Two guys by the entrance to Pirates got into it. They were swinging strollers at each other’s heads by the time security showed up.

“Hopefully with no kids inside.”

“Hey, you get enough adrenaline in you…”

“How do you know about these things?”

“I get bored. I chat. Most of the employees here are more bored than I am.”

“So what else do they tell you?”

“That, supposedly, the park is cracking down on misbehavior with expulsions and legal action. That there’s a low-level war going on between Spanish and Haitian cast members in the restaurants, and they’re thinking about banning motor scooters because of road rage. And I heard security have started carrying wristwatch tasers for serious infractions.”

“Infractions?”

“Aggression. Punching. Screaming. Fights. Family fights.”

“Yeah, I’ve seen those. More than once. Why is everyone so nuts now?”

“I think everyone’s a little stressed out about Shiva, right?”

“Shiva, yeah.”

“And, I don’t know, the economy, unemployment. I read somewhere that people spend three times as much at Disney when they’re scared of losing their job. Like, as a reassurance thing.”

The rain and wind suddenly intensified as if to get their attention, then receded into a soothing spatter. She yawned. He felt strangely awake.

“Listen Kirk, long day tomorrow. Treatment-team meeting, art therapy, the works.”

“Sure.”

“But we’ll probably run into each other again, right? Night.”

“Night.”

He parked the phone in its cradle, leaned back onto the pillow and tapped out a drum roll on his sternum. Shiva. He’d heard this word before, mostly in overheard conversations concerned the outrageous closure of rides. But at a certain hour of the night—after the squalls of magic hour, but not quite the last-ditch energies of closing time— he caught snippets of outside lives: drives, jobs, mortgages. Somewhere in these snatches of real-world concerns, this word had popped up. He’d dimly assumed ‘Shiva’ was another useless bit of pop culture. Brushing his teeth now, he wasn’t so sure.

In the lower lobby, a night clerk murmured to an exhausted-looking nuclear family, every member pointedly staring in a different direction. The concierge—Patricia—emerged from a back office, perhaps having sensed his desire for help.

“Yes?” she said with a peppy smile, unfazed by the hour.

“Yes, hi.” Kirk tried to match her smile. “I have probably the dumbest question you’ve ever gotten.”

“I strongly doubt that.”

“What is Shiva?”

The concierge flinched, as if catching the first whiff of a bad odor, saying, “I’m sorry?”

“I’ve heard this word a few…”

“Do you mean ‘when’?”

Kirk wasn’t sure what to make of this question. “I’ve heard people mention this word a few times, and at first I thought maybe it’s a popular movie or a, uh, you know, a video game or something.”

She placed a splayed palm on the counter. “Are you saying…” she looked down at the family, then lowered her voice. “You’re saying that you don’t know what Shiva is?”

“Yeah.”

“You don’t watch the news?”

“I haven’t followed the news in three years.” She squinted slightly, so he added, “I mostly watch movies on TCM.”

“So you don’t know about Shiva. The asteroid.”

He registered the same odd physiological reactions he’d had when he was younger and learning of catastrophe to come; a near-sexual rush of blood.

“An asteroid is going to hit Earth?”

“No, no.” She exhaled in seeming relief. “It’s going to hit Mars.”

“Oh. So this is… what? A scientific event?”

“I suppose you could call it that,” she said, searching his face for any giveaway that he was putting her on. “Mars will be destroyed. There could be some scientific value in that.”

“Destroyed.”

“This time next week, there will only be seven planets in the solar system. Or eight, if you count Pluto. Is Pluto still a planet?”

He pinched the bridge of his nose. “Destroyed?”

“Maybe this is something you should read up on.”

“I don’t have a computer or a cell phone.”

She looked around conspiratorially. “Listen. The business center is closed for the night, but you can use the computer in my office, if you’d like. I’m on shift for another two hours.”

She brought him to a corner of a large back office, to her surprisingly small and bare desk, leaving him, with one sympathetic squeeze on the shoulder, alone with her computer. He read about Shiva: a mass of nickel and basalt almost half the size of Earth’s moon, looping back into the inner solar system on an irregular, 6,000-year ellipse through nothingness. In its last hours of existence, it would pick up speed, approaching fifty miles a second as it plowed into Mars’s northern hemisphere. Shiva would impact in five nights, 9:42 PM on the East Coast, dawn for one of the Mars rovers, midafternoon for the other. It would take a quarter hour for the final transmissions of each feeble little robot to reach Earth.

He sensed a queasy relief that he alone hadn’t had to suffer through nearly two years of updates, each one upping the odds of galactic kamikaze. One in four million. One in four thousand. One in four. One in one. An email notification for Patricia popped up, and for a moment he thought he’d been found by someone from his previous existence.

Kirk spent the next morning on his favorite bench, riffling through the Anthology, skipping from Dryden to Pope to Heaney’s translation of Beowulf, none of it able to hold his interest, no author capable of speaking to his new mood. At eleven, he finally gave up, walked to the riverboat, and watched a fistfight between two families—heartland tourists versus wealthy Koreans—ending with a young-girl bystander receiving a spectacular accidental kick to the face. Both families gathered around the prone child, each bursting into huge whoops of tears as security surrounded their absurd huddle.

As the riverboat disembarked, he thought of days when real riverboats roamed real waterways, their real passengers witnessing real acts of violence on real riverbanks. He grasped an underlying truth: Disney World wasn’t built on nostalgia. No visitor cared about Twain or Norman Rockwell or the dozens of classic novels referenced in the rides; the park had become disconnected from its own mythologies. Parents brought their kids to the shooting arcade because they’d been brought to the shooting arcade when they were children. It was nostalgia for nostalgia.

He’d misjudged everyone. What he had thought was a system under stress was actually a people under stress. Everyone had had to live with a terrible knowledge that he alone had almost eluded: Summoned to respond to the loss of one light in the night sky, humanity had reacted with every stage of loss and grief.

He searched her haunts: Casey’s, the benches by the Enchanted Grove, the restaurants in Liberty Square. In the photo-spot clearing in front of the castle, he joined a crowd watching two women fighting and spotted Ava huddled, pigeon-toed, on a bench. For a moment, he thought she might be crying or drunk.

He sat down with showy caution. “What’s up?”

“Shane’s out.”

“Out?”

“He bought a pool bag, ripped out the lining, and wedged it between his ankle and the SCRAM bracelet. Something about the silica gel, how it mimics skin. Then he found somebody willing to sneak in a bottle of rum. Nobody’s really sure how that part worked. Maybe he just went around asking strangers, I don’t know.”

“Smart,” Kirk said.

She swung him a fierce gaze. “No, he’s stupid. Shane got so drunk he forgot to get rid of the evidence by lights out. Now he’s going back to Nashville and will probably have to serve time.”

Kirk thought about digging into the backstory on this, then decided against it. The nearby mob had dispersed, the two fighting women having melted into thin air.

“So we both had a shitty day.”

“I’m having a shitty ninety days.”

“If only there was someplace we could go to get away from it all, you know, with rides and ice cream and fun stuff.”

Ava smiled up at him. He had no idea how old she was.

“Let’s do a rain check,” she said, rising. “I’ve got nutrition counseling on It’s a Small World. That is, if they don’t make us all talk about Shane for nine hours.”

“Rain check,” he said, happy for the first time all day.

An hour after the park closed, his room phone rang.

“How was your thing?” he answered.

“I learned a lot about food triggers.”

“And it’s just a guy lecturing you? While you’re sitting on that little boat?”

“We had to sing along with his lyrics too.”

“Sounds like an expensive bummer.”

“You have no idea.”

“I never got to hear what it is you do for a living.”

“I was a model. I invested well.”

“Invested in what?”

“I don’t think I want to tell you.”

He paused to force her to continue.

“I was sort of the mascot for this wild little crew of fashion models. Women whose faces you’d know. I was the youngest, so I got to see every bad decision I could make before I actually made any. Divorce, bankruptcy, drugs. I didn’t want to end up like that, so I learned where to park earnings, how to maximize passive income. And now I own rental properties in six states.”

“Impressive.”

“And yet here I am.”

“Trapped in a luxury hotel.”

“Trapped in a luxury hotel room.”

“Tell me again. Why won’t they let you leave that room?”

“You never know what kind of trouble someone like me could get into, with my ‘addictive core narrative.’”

“Really? I mean you’re tagged and all. With that SCRAM bracelet.”

“Like a wild animal.”

“I was going to say, exactly like a wild animal.”

“You saw how easy it was for Shane to get his hands on some stuff. And that was inside the park, with all their security and all our group’s security. Imagine how easy it would be in this hotel. I heard some rooms have minibars.”

“Mine’s got one.” He winced, unsure whether he’d meant to impress or entice.

“Fancy. Deluxe or suite?”

“Deluxe,” he said, glancing around the space, trying to picture what its sloppy towers of books would say to a female visitor. “Extra chairs and everything.”

“And no one else, huh?”

“Just me, the wife, and kids.”

“Yeah, yeah, I can hear them screeching in the background.”

“Too bad you can’t come over and meet them.” He winced again, punching himself lightly in the forehead.

“Too bad I don’t get to take this itchy ankle monitor off. Unless I’m in the shower.”

He inhaled sharply, saying nothing.

“For all you know I’m in the room next to yours,” she continued. “Just listen for the water.”

On Tuesday, they made out. They held hands and kissed on Tom Sawyer Island, necked and kissed in the Hall of Presidents, groped and grinded in a dark moving pod in the Haunted House.

“I kind of like the hour-plus buildup of waiting in a line,” she said in the late evening, balanced on a bench-top, offering him a bite of a glossy-red candy apple. “But coming back out into the humidity and crowds is a bitch.”

The next day she had counseling sessions, and in the afternoon they decided to take things slower, mostly for the sake of slowing the mutual physical frustration. In the Enchanted Tiki Room, they found a corner that became their own after two sittings. During one viewing of the showstopper theme song—robot tikis gibbering like savages—a nearby dad turned to wife and kids, laughed, and yelled, “Ooga Booga!” Kirk didn’t mind the room’s mocking colonialism, but the moment when fake rain crashed down around the windows always made him swallow a lump of sorrow and anger.

“I think somebody wrote a book on the best make-out spots in the park,” she said on Thursday as they emerged, squinting and horny, into the midday glare outside the Peter Pan ride.

“I thought you couldn’t use a computer.”

“I can have Patricia order me books. That’s her job.”

The sun seemed to intensify as they passed through Cinderella Castle. A swarm of tourists parted, and when he beheld the silhouetted statue of Walt Disney, Kirk had another epiphany: The park was a vast cenotaph, a monument to one man far surpassing the extravagance of the Great Pyramids. A necropolis.

After dusk on Friday, they rounded a corner near the Country Bears and found Emmett and Carl leaning against a brightly lit wall, each holding large coffees, Carl looking like the structure was the only thing keeping him upright. Both men peered upward. Kirk followed their gaze, spotting only a distant speck of balloons floating into the night sky, connecting this visual to the sound of a child’s distant bawling. Carl looked at him with good cheer and said, “Fireworks coming.”

Ava seemed to ask the sky, “I wonder if they’ll stop doing fireworks when the debris field hits?”

“When is that?” Carl asked.

“Anywhere from one to three months.” Kirk shuffled a plastic bag into the bushes with one shoe. He’d read about the massive swath of dust and rock that would eventually cross into Earth’s orbit. Experts predicted nightly light shows and shooting stars for years to come.

Emmett cleared his throat. “One to three months? How come that’s so goddamn imprecise?”

“Because no one knows exactly how this will work,” Kirk said. “Nothing like this has ever happened in human history before.”

“So what? There’s never been a global warming in human history, and you guys are perfectly fine telling everyone how that’s supposed to work.”

Seeing Kirk squint, Emmett added. “Oh yeah. Your girlfriend told us all about your book.” Ava shrugged sheepishly.

“What, you guys needed even more of our tax dollars?” Emmett had balled his fists. “Is that it?”

Kirk rubbed a forearm nervously. “What are you talking about?”

“I’m talking about NASA building rockets to blast Martian asteroids, when everyone knows the odds of that happening are a half billion to one. You think that shit is free? American taxpayers pay for it. I pay for it.” He jabbed his chest next to the dangling “Happy Birthday” button he’d never bothered to remove. “And who’s going to pay us back for all the rovers and satellites we sent to Mars in the first place, huh?”

“Emmett, I don’t know where you’ve been getting your facts,” Ava explained. “But the odds of a big chunk of Mars hitting Earth are one in 140.” Kirk nodded emphatically. He’d read this as well.

“Check your math, brainiacs,” Emmet said. “The odds of Mars being destroyed were one in four million. The odds of a dangerous fragment hitting Earth are then one in 140. Four million times 140 is close to a half billion. My odds of hitting Powerball are better.”

Kirk gripped his own arm again.

“I don’t think you know how math works.”

Emmett spit something out of the side of his mouth and took a step toward him.

“Yeah? Why don’t you tell me? Explain to me how math works, if you’re so much smarter than I am.”

“Come again?”

“‘Save the ozone!’ ‘Oh, no, Earth is melting!’ “The sky is falling, save us, NASA!’ And yet none of you have any numbers to back up your bullshit. Know why? Because it’s just one more scam to whittle away at my profit.”

“What profit are you making if you’re in here?” Kirk said, trying to sound calm. “You’re not working.”

Emmett squinted and blew into the little hole on his coffee lid.

“Well then, it’s guys like you who are skimming off the interest my bank account makes while I rot in here. Every week a new tax.”

“And you’re someone who’s spent his whole life drawing off the world’s principal, thinking it was interest.”

“What the fuck does that mean?”

“Emmett?”

All four turned to see a portly young couple, the young man standing with arms stretched wide.

“Don’t you remember me? From ten years ago?”

The man’s companion stood with a hand over her mouth, trying not to laugh.

“I don’t know you,” Emmett said quietly.

The young guy held his pose for a long beat, then broke into laughter. “Naw, bro, I’m just messin’ with you.” He tapped his chest, just above where his own shirt read “HIGH HO, HIGH HO, IT’S OFF TO TWERK WE GO.” “I saw the birthday button with your name, so…”

The young woman was laughing now. “He’s been doing this all day, guys.”

“I don’t know you,” Emmett repeated.

“Naw, it’s cool, it’s cool. I’m just messin’”

Kirk saw Emmett’s thumb pop the plastic lid off his coffee cup, watched as he flicked the full cup into the young man’s face, saw Emmett’s fist connect with that flabby gut even before the young man could compose a full scream.

Somewhere in the slo-mo of adrenaline, security materialized—two plainclothes, two in official park outfits—Kirk heard a muffled “Oof” and then saw Emmett slump forward in their arms. Another security guard led the young couple to a bench and mumbled “Medic” into his sleeve. After they realized Carl had scampered off somewhere, Ava and Kirk found their own bench and sat in shaky silence, each half-shaded in one of the quaint little bowers of light and shade the park formed each night.

“Yeah,” Kirk finally chuckled. “So then there were two.”

“Huh?”

“Emmett and Shane. You’re down half the group.”

“Oh, Emmett won’t get kicked out for this.”

“For assault?”

“Life Journey LLC has a pretty ironclad arrangement with the Disney people. We get kicked out for breaking our rules. Not theirs.”

He heard the first pop of fireworks somewhere far behind him, and a weak blue light illuminated the leaves near her cheek.

“How does that work?”

“This program costs two grand a day is how that works.”

He whistled. “What kind of rehab program is this?”

Ava paused to compose her words.

“Carl had a blood alcohol of 0.19 the night he backed over a fifth grader. Shane got blitzed on a cross-country flight and broke a stewardess’s jaw. Emmett drove his Jaguar from a bar to his local liquor store, continued through the front window and straight down the middle aisle. Killed two people.”

Another firework cracked open far above.

“I guess I don’t want to ask what you did.”

“Yeah,” she continued, almost whispering, still not making eye contact but gripping his hand tightly. “This is where the shits go.”

He jolted awake at dawn, showered in a stupor, made coffee, found a news channel, and watched a cartoony computer graphic of two brightly colored balls colliding in space, as if they might simply bounce off each other. He whispered, “Boioioiong,” then covered his mouth in shock. The weight of what was happening came on like nausea. A clock in the corner of the screen read, “13 HOURS 48 MINUTES.” He had to get outside.

Kirk tracked her down at dusk, at the same table where they’d made introductions a week ago. He’d spent hours wandering, and as he approached, he realized he had no recollection of the day, only that he’d spent it on the move, and that his feet hurt, and that he wasn’t even carrying a book. A travel bag sat in the chair next to her.

Sensing her mood, he tried to make himself sound upbeat. “Going somewhere?”

Without smiling, she handed him a receipt. Small, cheery type announced: “POOL BAG $449.”

“I want you to get me a drink.”

“What?”

“I want you to take some liquor from your minibar, pour it into a soda cup, and let me drink it.”

He palmed and massaged his eyelids.

“Just this once, Kirk. This one time.”

“Jesus. Ava…” He couldn’t think of a response. They sat in silence. Finally, she said, “Yeah, no, I get it. I suppose that wouldn’t be ‘honestly and effectively assessing and addressing my grief.’”

Kirk froze. She was quoting him.

“Or would having a drink be ‘a new tool for coping with catastrophe’? I’m confused now. Which is it?”

“How did you…”

“I had Patricia order me your second book. I read Grief of a Species in two nights. I told you, I’ve got lots of time on my hands. It’s very dishonest of you, you know. Demanding that people surrender rather than try to deal with their problems.”

“First off, I want people to stop surrendering to false hope. Secondly, deal with how? You understand there’s no longer any way to halt or deny what’s going to happen to us, right?”

“Kirk, you have a whole chapter dismissing solutions to global warming. That thing with dumping metal dust into the ocean for plankton.”

“Iron fertilization…”

“And spraying sulfur in the upper atmosphere.”

“Geoengineering…”

“You trash all these concepts on the grounds of what, exactly? You can’t fight technology with technology?”

“More or less.”

“Why? If geoengineering brought down the world’s temperature, why not do it?”

“Because it would just spur people to create more CO2. It’s the easy way out, the one that encourages even more mindless consumption”

“So what?”

He whistled in disbelief.

“You know what your book reminded me of? All those preachers who want to fight AIDS through abstinence.”

“Really?”

“Look.” She pointed to a mother and her daughter. The girl was five or six, walking dopily from fatigue, an oversize, self-lit Mickey balloon following her like an errant thought bubble.

“According to you, that kid is going to grow up in a world of refugees and disease and famine. That’s not her fault. But by your logic, she should be punished for living a life she knows no alternative to.”

He took in the pair, proxies for his entire thesis. Ava turned to face him again.

“Or maybe you think the mom is the one who should be punished? For being a mom in the first place.”

He raised his eyebrows and finally shrugged.

“Yeah. You won’t charm any ladies with that argument.”

“Do you have any idea how many times I’ve had these arguments in the first place?”

“I’m guessing zero since you moved to Disney World. You know what I think? I think you want to wallow.” She stretched this last word, making it three syllables.

He ran his tongue along dry lips

“So why can’t I wallow, Kirk? Not for three years, like you. Just tonight, the one night in my entire life that something is taking place that is truly terrible and terrifying and so fucking massive that I can barely get my mind around it. I just want to go sit in room and get blitzed. I’m not driving. I’m not online. I’m not hurting anyone. I’m just addressing my grief.”

He dropped his eyes to the table.

“Or maybe you think I’m just the wicked woman who’s played you for a drink? Huh? Just another harpy con artist?” She grunted in disgust. “Jesus, dude. How fucking predictable is that?”

On the monorail, he studied the dull-gray flooring, trying to sift through what exactly she had made him feel. Mostly there was humiliation. Not so much for what she’d said than at himself, for having given anyone leverage over his life.

He looked up and saw the train was packed. He was familiar with the exhausted silences of late-night monorail rides. This silence was different, expectant, everyone riveted to small screens, the blue squares reflected against the last red and orange slashes of sunset in the windows.

In his room, he paused in the unfamiliar light. He’d often seen the space at dawn, the severe shadows or glints, depending on which direction he’d faced in his sleep. But now the windows were squares of bluish glow, giant phone screens weakly illuminating the bulges and outlines of his living quarters. Beyond the silhouette of the patio railing outside, he could just make out a corner of the vacant pool area. What was a “pool bag” anyway?

The minibar had never meant anything to Kirk besides a motor whose white noise soothed him to sleep every night. Opening it now, he saw the same fresh orange he’d seen on his one and only inspection, the night he’d moved into the room, three years ago. Replacing this must have been a ritual for one of the cleaning people. He grabbed one mini-bottle of vodka, closed the door, then reconsidered and grabbed three more. On his way out he realized they were tinkling against each other, so he put two in each pocket and stuffed a handful of tissues in after them.

A family sat crying on the monorail ride back to the park. From the other side of the train, someone said, “It’s happened. We just have to wait for the footage to reach us.” He wondered where he’d been when Shiva exploded into Mars. On the first monorail? In the lobby? Opening the door to the mini-fridge? Had there been a second—an instant, a microsecond—when the two celestial objects touched? Or was it all heat and light?

From the train, he caught a long glimpse of a candlelight vigil. Crossing down from the platform, he discovered several hundred faces in the courtyard before the ticket booths, each illuminated by a tiny screen. Everyone waited to see what had never been seen before, the visuals from a dying planet filmed through the eyes of two rovers that were themselves now nothing more than cosmic dust.

A small queue stood in front of the only open ticket booth, each person stepping backward slowly, enthralled by this unscheduled spectacle. Kirk moved backward as well, and when an employee asked for his pass and fingerprint, he pulled out his wallet, hearing something fall to the pavement with a loud tinkle. The booth clerk—young, androgynous, acne-riddled—said “Security” in a bored voice. Even as Kirk saw his tiny bottle held aloft, even as a tall woman in the crisp blue shirt of a security officer arrived and inspected the bottle with an air of detached disapproval, Kirk simply didn’t think to connect these events to the actual life he was currently living.

“Sir. Is this yours?”

He finally focused on the bottle, understanding that his participation was required.

“Not exactly.”

“Not exactly,” the woman repeated, ushering him out of line.

“I mean, yeah.”

She brought him to a long folding table thirty feet away and produced her own glowing tablet. For a moment it looked as if she were joining the vigil.

“Empty your pockets, please.”

He weighed his options, slowly removing the other bottles, lining them neatly on the table next to his meager wallet.

Two nearby men in security attire turned their gazes from the silent crowd to stroll over. Their badges bore small mouse-ear insignias, and he considered that their presence was just one more bit of street entertainment. Overhead, red and white fireworks blossomed with a loud fizz. A few faces in the crowd turned to acknowledge the show, then dropped back to their phones and tablets. The main security guard said, “I need a print, please,” as she gently directed one of his fingers into a portable hand scanner.

He wondered what that transmissions from Mars would look like, picturing a new moon growing larger and larger until it blotted out the sky. Or, worse, rushing up all at once, just a glimpse of oblivion and then blackness. How fast was fifty miles a second?

Another firework crackled far above them, illuminating the silent mob like slow lightning.

“Okay. Sign here, please.” She handed him the tablet and a stylus.

“What is this?”

“This just indicates that you violated park rules. Pretty standard.”

He signed. The two other guards glanced up at the fireworks.

“So, I’m free to go in now?”

“Oh, no. You’re expelled. We’ve deactivated your pass.”

“What? No, no, no.”

“Sir, you just signed a statement to this effect. Did you not read the statement you just signed?” A flare of green lit up her face and ridiculous badge and the four guilty bottles of vodka behind her.

“You just watched me sign it without reading it,” he said, trying to control the waver in his voice. “Hold on. I’m a long-term resident of the Contemporary. The hotel is for park guests. So I can’t be expelled.”

“If you’ll let me finish, sir, Kevin here will escort you back over to the hotel and allow you to gather your things. The front desk has a list of other suitable hotels in the Orlando area.”

“No, wait. Wait.”

“Sir, you need to—”

Somebody screamed from the far side of the courtyard. It was a keening wail, something far rawer than any park meltdown or brawl he’d ever witnessed. A gaggle of teenagers closest to Kirk erupted in shock at the scene playing out on their own screens, one boy in a sideways baseball cap yelling “Oh shit! Oh shit!” and staggering backward. Then the mass erupted in imperfect unison, howling, bawling, some covering their mouths in fear, a few dropping to crouch on the pavement, some staring in mute horror at the images before them.

Another firework bathed the scene in sickly yellow. He looked up to view a fading star of sparks illuminate a tangle of drifting smoke. More fireworks burst, and Kirk saw the display for what it was: Flares shot into the night. He pictured the scene from overhead, zooming out, farther and farther, until the fireworks were barely a dot, meager distress signals for the help that would never arrive.

Originally published in Apology #4, Fall 2015