As told to Robert Polito and Karin Roffman

Photos by Brian Deran

John Ashbery is America’s greatest living poet, and that’s a quantifiable fact—if prizes can be used to gauge such things. Ashbery has won the Pulitzer, the National Book Award, a Guggenheim Fellowship, and more. He’s received official accolades beyond counting, really, starting with the publication of his second collection, 1956’s Some Trees, which took the Yale Younger Poets Prize.

But prizes aren’t what matters. The work is the thing, and Ashbery, over the course of seven decades writing, has built an oeuvre that is vivid beyond imagining. A revolutionary in form and in language, an iconoclast and an experimentalist to the core, Ashbery has always written poetry that stands up, radical and daring, next to anything being produced by the generations that have followed him. As poetry has wound and twisted through movement after movement, Ashbery has remained a constant source of surprise and beauty. Free, playful, funny, filled with reference and complication, his poems challenge us—they sometimes even baffle us—but they never sacrifice the pure thrilling mastery of language that reminds us that we’re dealing with the real thing—a poet to the bone, a vessel for the cosmic muse.

Recently, Apology had the chance to visit Ashbery at his home in Hudson, New York. He lives with his longtime partner David Kermani in a stone and clapboard house that faces a small park. Their home is full of art and objects that have been collected by the pair over the years. It’s a gathering of such interesting things with such great stories behind them that the New School in Manhattan is currently in the midst of a project that will document and catalog all of it.

We sat, first in the downstairs music room and later in an upstairs sitting room, with Robert Polito, the head of the writing department at the New School and the steward of the Ashbery cataloguing project; Karin Roffman, who is currently at work on a biography of Ashbery; Kermani, and, of course, John Ashbery himself. We spent the afternoon listening to stories from him about some of his favorite things. Before we get

to them, however, let’s hear some thoughts from Robert and Karin…

ROBERT POLITO

ASHLAB is an ongoing project at the New School that proposes a digital mapping of John Ashbery’s Hudson house via his work—and the reverse: a digital mapping of his work via that Hudson house. I conceptualized ASHLAB during the fall of 2011, after conversations with the generous, gracious, and resourceful David Kermani, and launched a multiyear sequence of courses with an expert instructional team composed of two brilliant poets, Tom Healy and Adam Fitzgerald, and a genius information and interaction designer, Irwin Chen. Our students work on various Ashbery-inspired operations—annotating objects in the house, such as paintings, curios, architecture, and mementos; anthologizing and annotating poems according to various subjects and themes, such as music, childhood, art, cinema, games, architecture, or nature; and defining and mapping routes through the house and work, his prose as well as his poetry. The courses are inherently multidisciplinary, drawing graduate students and undergraduates from across the New School—the Writing Program, Parsons, Media Studies, and the Riggio Honors Program: Writing & Democracy. How is it possible, these courses ask, to archive and map the interiors of (arguably) America’s most important and influential living poet, John Ashbery? I’ve come to think of our adventure as spanning three houses simultaneously—a literal house upstate overflowing with objects, art, people, and continuing production; a virtual house, someday to reside on the internet, where students and faculty will represent, document, and annotate those objects, art, biographies, and artistic productions; and finally a sort of metaphoric house, accommodating Ashbery’s digital archive, with many routes leading from and into Paris, nineteenth-century upstate New York, and twentieth-century painting, music, literature, and film. ASHLAB in that respect can be approached as a Memory Palace, in homage to those imaginary spaces Renaissance philosophers such as Giordano Bruno or the Jesuit missionary Matteo Ricci, advanced for storing and retrieving memories from visualized locations along chains of resonant associations.

KARIN ROFFMAN

My work on John Ashbery’s biography began in 2005 as a project on Ashbery as a poet and collector in his Hudson house. I knew Ashbery only from his poems and so, like many other first-time visitors to his home, I was quite surprised to discover that this very contemporary poet lived in a dark and gloomy 1894 Victorian. In 2009 I received an NEH Summer Stipend to deepen my research and writing on the house, and it was during that summer of interviewing Ashbery and David Kermani on the provenance and history of objects and collections that I also, without initially realizing it, began to research my book on Ashbery’s early life. Everybody’s home is autobiographical in some way; Ashbery’s much more than most. His numerous and eclectic collections are personal, carefully chosen and artfully arranged—often most when they don’t seem to be—and assembled from a combination of objects his parents and grandparents once owned, works his artist friends gave him, accidental discoveries (including things abandoned by the family who originally owned the house), and Ashbery’s own purchases. The house is both a sly performance of autobiography and—since he really lives in it, uses it, loves it, alters it, and is inspired by it—a practice of it. It is the only home Ashbery has ever owned and is the realization of a process and practice of collecting and thinking about decorating houses that he began as a young boy living on a farm in upstate New York. At 13, he spent long days antique-hunting with his great friend Mary, explored old houses with his childhood playmate Carol, borrowed books on decorating from family friends, and lay each night on his twin bed conjuring in his mind all his plans for the kind of physical, emotional, and imaginative environment he hoped one day to create and inhabit.

John Ashbery: I got this in Paris. It’s Daum. Nancy, France, is where the Daum glassworks is, so people always say “Daum Nancy” together. My friend James Schuyler once wrote a poem called “Who is Nancy Daum?”

Anyway, I think that Daum is still in business. They’re particularly renowned for their Art Nouveau period. This is obviously a winter scene, with the sort-of sickly winter sun setting in the right. There’s also another socket in it, which lights up the base of the lamp, but I’ve never been able to find a bulb to fit it. I used to have one I got in France, but I don’t think they make them here.

I lived in France for about ten years. 1955 to ’65. I had a Fulbright for one year, then it was renewed for a second year. Then I actually came back to New York and took some graduate courses in French at NYU, with the idea of going back and doing a dissertation on Raymond Roussel, a writer I had discovered thanks to my friend Kenneth Koch. And I did a lot of work on that before realizing I didn’t really want a PhD—I just wanted to live in Paris.

I had very little money all the time I was in Paris, so I couldn’t buy any of the lovely objects I would see in store windows. And I never thought I was going to come back with more money. I had just enough to barely live. But then I went back in the fall of ’68 for three months; I had a Guggenheim Fellowship and a little extra cash, so I picked up a few things—including this lamp. It was in an antique store, I think on the Boulevard Saint-Germain near Saint-Germain-des-Prés. There was another very beautiful lamp there that I could have gotten, by a lesser-known glassmaker called Muller. The base was all glass mosaic and the shade was blue and yellow. It was really beautiful. But I guess I thought that Muller wasn’t famous enough. [laughs] So I bought this one instead.

I’ve always been interested in trompe l’oeil objects, like this dish with a faux nutcracker and walnuts and that other one which has a dice cup and dice, which was given to me by a wonderfully eccentric old English lady who lived in Hudson when we first were here. Her name was Edith Lutyens Bel Geddes. She had been married to the designer Norman Bel Geddes. She reminded me of Madame Arcati in the Noel Coward play Blithe Spirit.

This was given to me by de Kooning, I believe, via his dealer. I was an editor at Art News for a number of years, and I wrote an article about de Kooning’s lithographs, which he didn’t do many of. That series was all black-and-white, which had some connection with a trip to Japan he’d made at the time.

I never really could understand how lithographs were made, so I went to the firm that was making these for him, and the owner explained the lithography process, and I still didn’t understand it. So he said, “Why don’t you make a lithograph and then you’ll know how to do it.” So I actually did, and I still couldn’t understand it. [laughs]

Later, a friend of mine, Gerrit Henry, a poet and art critic, got a job at Art News and I went to see him at his office one day. I noticed that on the bulletin board was my lithograph—signed by me. I said, “Where did that come from?” Apparently the lithography company had sent them all to Art News, which had never bothered to give them to me. So I at least got that one.

I like very much that score that’s over on the piano, which is for French nursery rhymes, with beautiful drawings by an illustrator named Louis-Maurice Boutet de Monvel. He was one of a bunch of marvelous early-twentieth-century illustrators. Edmund Dulac, who was mentioned in a Yeats poem, was of course another. And George Carpentier, who did fashion illustrations.

Neither of these is original. The one, I think, is a plaster copy of a bust by Houdon. The other one I once thought was an original by Philippe-Laurent Roland. But I showed it to someone I know who is a specialist in French sculpture at the Met, who said it’s a fake. I guess these were very popular for decorating purposes around the turn of the twentieth century, when faux-eighteenth-century stuff was in style. In fact, a lot of furniture in this room is in that genre.

My favorite piece of furniture in this room is that little sofa over there, which is the one genuinely eighteenth-century piece in here. I got it from an antique dealer who sold me much of the stuff that I own, Vito Giallo. He’s still in business, I think—not in a store, but online. He was a very nice guy with an incredible eye. He had a series of tiny little shops on the Upper East Side. I used to drop by almost every week to see what new things he’d got in. He was wonderfully open and, well, unaffected—considering the sophistication that was evident in his eye. Not what you would think of when you hear the words “Upper East Side antique dealer.” He was very basic, nice, and honest. And he also charged way below the market rate for his stuff, which is one reason why he was so popular. He was extremely sought after by, among others, Andy Warhol. Vito and Andy were actually roommates when they first came to New York—long before anybody had heard of Andy. And then there were these society matrons who were always referred to as “Vito’s ladies.” They were always there pestering him.

When I was first living in New York after moving back from Paris, I lived in a brownstone that belonged to the abstract expressionist painter Giorgio Cavallon and his wife, Linda Lindeberg, who was also a painter. They were friends of Rothko,

who was a neighbor of theirs—just in the next block, actually, on 95th Street. It was they who told me I should check out Vito’s store. Rothko was also one of his clients.

Jean Hélion was a painter I always found fascinating, even before I went to Paris. And when I got there I actually got to know him. We became quite good friends, and he gave me a number of his works. He was born in 1904, I believe. Although he was well known in France, he never really had the reputation he should have had—in my opinion and also in his. I frequently wrote about him for Art News and the Herald Tribune, among other places. He was very grateful for the attention. His widow has just brought out a catalogue raisonné in Paris, actually. She’s a wonderful person, half French, half American, but I think she’s lived in Paris most of her life.

Anyway, Hélion, in the late 20s and early 30s, was an abstract artist. He kind of gravitated toward Mondrian. And at that point, nobody was interested in that kind of art in Paris. Then, in the mid-30s, when they finally were, he had moved toward figurative art. In 1943, he was a prisoner of war in a German prison camp. He somehow escaped and made his way to America, where I think he had already lived in the 1930s. He wrote a book about his escape, called They Shall Not Have Me, which became a best seller in the U.S. I think he was married then to an American woman in Virginia. But I’m not sure of the details. After the war he became sort of semi-abstract, I guess you could say, and finally a realist.

The large painting of a rose is by Alex Katz. It’s a fairly early painting, and it was a gift from him. It’s from 1966.

I’ve always been attracted by figurines like these. The two dogs are Staffordshire. The bride and groom on the end are also Staffordshire. There’s a GI, but I don’t think he’s Staffordshire. And there’s Daffy Duck, one of my cultural heroes. There’s a little painting behind them all by Fairfield Porter. It’s a sort of talismanic painting, I think, of his. He always kept it on the mantel in his living room. It shows the shore of the island in Maine where he had a house. I should take those vases out, so that one could see the painting. And there’s a Trevor Winkfield collage hanging on the wall above all of it.

The paintings on this wall are all by women artists. So I think of it as the “Women’s Wall.” The one on top is by Elaine de Kooning. It’s a sort of abstract landscape, which I believe was a gift from her. And the one underneath is by Nell Blaine. The one in the middle is by Anne Dunn, an English friend of mine. And the still life on the end is by Jane Freilicher. It has a copy of Art News in it. I forget exactly how it wound up in my hands. I’m sure she gave it to me, but I forget when, or whether there was some connection to when I was at Art News.

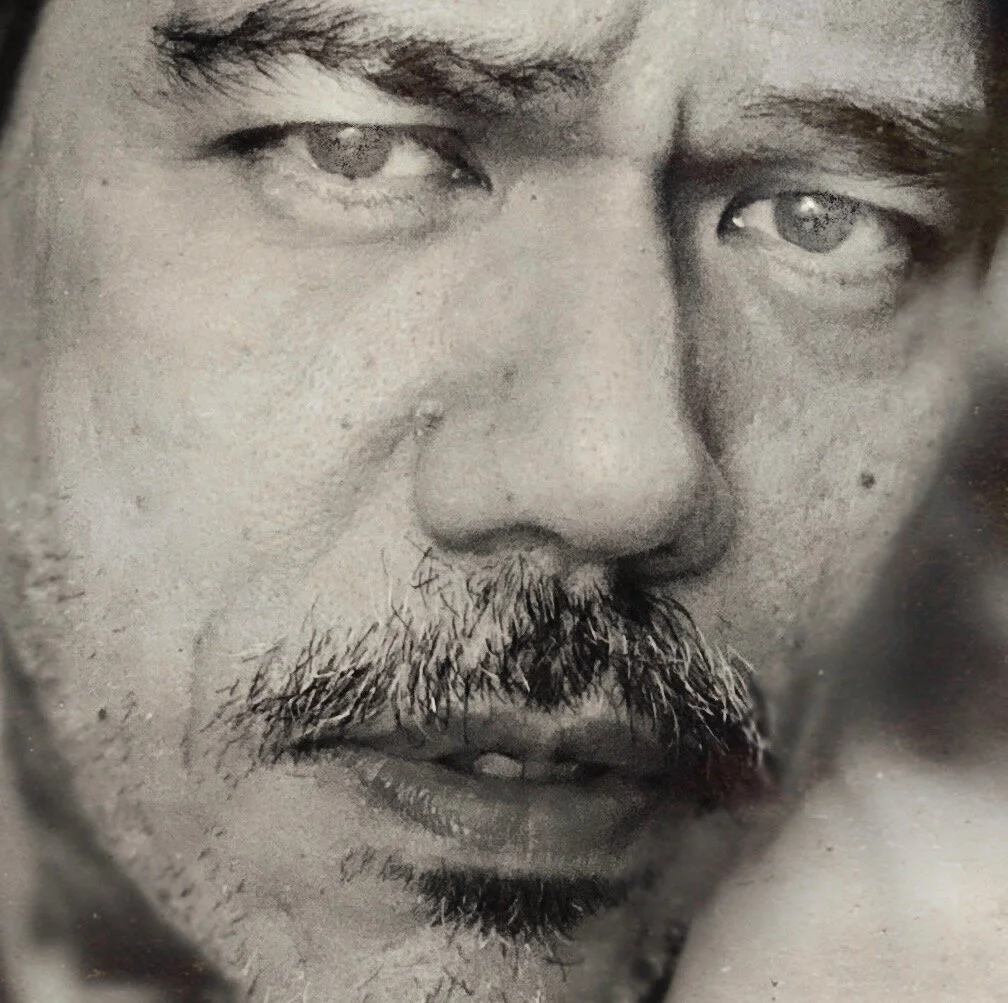

I don’t exactly remember sitting for this portrait. It was done by the painter R.B. Kitaj, who was a friend of mine, and whose work I liked very much. He also did portraits of the poets Robert Duncan and Robert Creeley, who were good friends of his. He was another case like Hélion. He was well known, but it seemed he was never well known enough, both to me and to him. He was also figurative when everybody was abstract. He lived in London for many years. I wrote several articles about him. In one of them I compared him to other American gadflies in England—Whistler and Ezra Pound. Like them, he too was constantly warning against English stagnation and impending Americanization.

He finally had a wonderful retrospective exhibition at the Tate, which later came to the Met in New York, but which a number of English critics panned. And then his wife, who was younger than he was and also a painter, died suddenly. I think he felt that her death was partly a result of the attacks on him. He was very angry about that. So he uprooted himself and went to live in LA. He died in 2007.

At one point I decided I would collect miniature shoes. One of those pairs, at least, belonged to my grandmother. The ceramic ones with flowers on them. Maybe I decided that would be the foundation of a new collection. And it’s quite easy to find miniature shoes, it turns out. James Tate, the poet, a good friend of mine, collects them, and I think that’s what gave me the idea. He has a lot of eccentric collections, too.

I remember sitting for this. I was about 30 at the time. I think I was spending the week at the Porters’ house in Southampton, which I frequently did. That was during the winter I spent back in New York, after my first two years in France. I was probably feeling very depressed because I wanted to be back in Paris. I was probably trying to figure out ways to get there. If I do have a favorite portrait of myself, I guess it would be this one.

I like David’s bronzed baby shoes. They somehow express his personality. I think I’d better not elaborate.

Originally published in Apology #1, Winter 2013